Have you ever wondered why an event usually has to happen before action can be taken? Why it is only after an event that precautions are taken to ensure that the impact of such an event is not so far-reaching should it occur again? This question is addressed in this blog article. First and foremost, in order to address a risk, it must be known. In some companies, this is proactively investigated and risk analyses and business impact analyses are done. But why are some risks not taken seriously or addressed, even though they may be known?

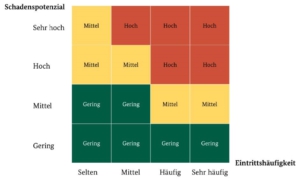

To begin, let’s review how risk is defined in emergency and crisis management. A risk is the probability/frequency of occurrence of a certain event times its damage extent/potential. The various risks are classified in a risk matrix, which is used as an assessment template.

Fig. 1: Risks mapped in a risk matrix according to their

respective damage potential and frequency of occurrence.

This risk matrix serves as the basis for further risk categorization. It shows how critical the particular risk is. If the risk is in the red zone (high risk), risk-reducing measures should be taken; if the risk is medium (orange), various options for action are open to the company. All this sounds like a very objective process, but is risk something purely objective? Does each of us perceive a possible event as equally serious? In other words, does each of us have the same perception of risk? No, the answer is no, because risk perception is subjective. It is the personal assessment of risks. Risk information is assessed differently from person to person depending on cognitive, emotional and motivational evaluation.

The fact that risk perception is not objective will be illustrated here with a few examples: for some people riding a motorcycle means such a big risk that it stops them from getting on one, others hardly see any risk in it, and still others see the risk but are willing to take it. Another example, to stay with traffic, is the risk of an airplane accident. From a purely statistical point of view, it is safer to fly by plane than to drive by car. Nevertheless, the perception of risk is often the other way around. For many, getting on a plane means a much higher level of stress than driving to the airport. On a purely rational level, this is not comprehensible, but if you include the emotional evaluation of an event, which varies from person to person, a different picture emerges. Driving a car is something we do every day, the risk is known to us and we are prepared to take it. Flying, however, is even more contrary to human nature. In other areas, too, an often illogical perception of risk takes hold. Sharks, for example, are feared, even though attacks with a fatal outcome are extremely rare. The probability of being hit by a falling coconut is higher than being attacked by a shark. Assuming the highest possible level of damage for both, i.e. the death of a person, the risk of being hit by a falling coconut and subsequently dying is higher than experiencing a fatal shark attack. Nevertheless, swimming in a shark area evokes greater fear in most people than lying under a palm tree.

It is precisely this personal connection that is the reason why action is often only taken after an event has occurred. If there has not yet been any contact with the risk, the probability of occurrence is considered to be lower and the risk therefore appears lower in the matrix. After an incident has occurred, there is a reference to one’s own actions in addition to the subjective relevance. Also playing into the risk perception is how well a person knows a subject area and has accordingly dealt more with dependencies, functionalities and possible influences.

Thus, there can be a significant discrepancy between a risk and the risk perception. The reception and processing of directive sensory perceptions or information in relation to the risks ensure that it is not solely rational, but also underestimations and overestimations or even a blocking out of a risk can take place. The human being has as a goal to cope with the risk information in order to achieve a reduction of anxiety. Whether or not this coping is functional remains to be seen.

In order to be able to assess a risk as objectively as possible, it is therefore worth taking a step back and breaking down a process into its individual parts so that all dependencies can be captured. This ensures that a hazard is broken down in its complexity and thus smaller disruptive factors can be identified that may have an impact on the process. If the single processes of the company are well defined and understood, the probabilities and impacts can be determined more easily. It is also helpful if an external view is taken so that risks can be considered that are not obvious at first glance. How to deal with the individual risks identified depends on the company’s risk strategy. Opportunities can arise from some risks, while other risks are unacceptable and must be addressed through measures that reduce the probability of occurrence or the amount of potential loss.

If you would like to receive support in an objective risk analysis with as complete a picture as possible, please feel free to contact us!