Many commentators referred to the COVID-19 pandemic as a “Black Swan” event. However, this is a misunderstanding of what a Black Swan actually is. Understanding the difference moves COVID-19 from the list of events for which governments and organizations could not prepare to the list of events for which they should have prepared.

What are Black Swans?

The theory of Black Swan events was developed to categorize unpredictable high-impact events. Nassim Nicholas Taleb first proposed the term in his 2001 book Fooled by Randomness. In 2007, he expanded the concept in his better-known book, “The Black Swan.”

According to Taleb, a Black Swan event has three characteristics:

“First, it is an outlier, being outside the range of regular expectations, because nothing in the past can convincingly point to its possibility. Second, it has an extreme impact. Third, despite its outlier status, human nature lets us concoct explanations for its occurrence after the fact, making it explainable and predictable.”

Why COVID-19 is not a Black Swan

There are many articles from recent months claiming that COVID-19 is a Black Swan, but even a glimpse at Talib’s definition shows that COVID-19 cannot be a Black Swan. Why? Taleb says that for an event to be classified as a Black Swan, “nothing in the past can convincingly indicate its possibility.”

If we break this down further, we have seen pandemics frequently, the last one just a decade ago, in 2009. So a pandemic was absolutely predictable.

Recent pandemics have been caused by flu viruses, for example. Does this mean that the current coronavirus pandemic was unpredictable and therefore a black swan? Again, this is not the case. Scientists have recorded evidence of possible previous coronavirus pandemics. The SARS coronavirus outbreak that began in 2002 left the world nervously hoping that it would be brought under control before it reached pandemic status. A future coronavirus pandemic was entirely predictable, and even if it was not designated as such, national risk registers, such as the UK government’s, contained separate entries for “Pandemic Influenza” and “Emerging Diseases.” In essence, the potential for a pandemic originating from a non-flu source was clearly identified.

In fact, in a March 2020 article, “Corporate Socialism: The Government is Bailing Out Investors & Managers Not You,” Taleb himself confirmed that COVID-19 is not a Black Swan.

“Had they read this book [The Black Swan], they would have known that such a global pandemic is explicitly portrayed there as a White Swan: something that would eventually happen with a high degree of certainty,” the article states.

High consequence, low probability events

Why is it challenging to prepare for high-consequence, low-probability events? Part of the answer has to do with the innate human tendency to focus on immediate threats rather than risks that seem far in the future. Imminent low-probability threats seem more important to us than high-probability events that we have difficulty imagining. We humans tend to assume that such things are unlikely to happen to us. If we determine, based on current experience, that a severe pandemic is a once-in-a-century event, it would be recorded in a risk register as a high-consequence, low-probability event. Something with extreme impact, but unlikely to happen in a given year. Because of this human tendency, organizations often focus on probability rather than consequence, mistakenly viewing the likelihood of a once-in-a-century event as one that will occur many years in the future and therefore can essentially be disregarded.

David Ropeik, a well-known consultant and public speaker on risk perception, risk communication, and risk management, describes this phenomenon in the article “The Psychology of Risk Perception.” Are we doomed because we misperceive risk? and states, “We count on a system of risk perception to save us that is better suited to protect us from snakes and darkness than global abstractions riddled with technological complexity and unknowns.”

This results in what Ropeik calls “optimism bias” – human instinct is “overly optimistic about what lies down the road when the details are unclear.”

This instinct also leads organizations and even governments to not take high-consequence, low-probability events as seriously as they should, with the result that they cannot plan effectively.

Looking ahead

What other high-consequence, low-probability events should we prepare for?

Are there other high-consequence, low-probability events that society is currently effectively ignoring?

Unfortunately, there is a long list.

Consider the following, all of which are predictable and some of which are inevitable (the only question is when, not if). How many of these has your organization considered and how many have you planned for?

- An H5N1 pandemic

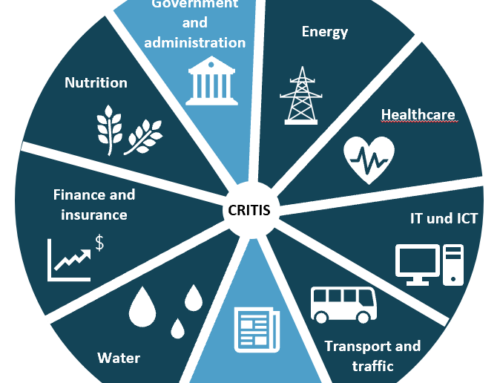

- A highly successful cyber attack on critical infrastructure, such as utilities or one of the largest cloud computing providers

- A chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN) attack

- A major earthquake (in California)

- A severe solar storm

- A major volcanic eruption

There is another category of high-consequence events: those that are not low-probability events that we can see are already underway but are slow to develop.

The COVID-19 pandemic is causing business continuity professionals to question the industry mantra that scenarios should not be planned for, only the impact should be considered. However, this approach may have been ineffective for the current pandemic.

Business continuity experts are beginning to accept the importance of playbooks – specific plans for specific scenarios where an impact-only approach does not provide enough specificity for effective business continuity.

However, scenario planning should always be approached with caution and balance. Although helpful for situations such as COVID-19, it is preferable to think of scenario planning as supporting impact-based planning.

We don’t want to go back to the useless 100+ page plans of the past, do we? Together, the two approaches can provide broader resilience while avoiding those gigantic plans.

For now, consider whether your organization would have benefited from a pandemic “playbook”? And would they benefit from a playbook for the other large-scale threats we’ve discussed here? Perhaps they are “inadvertently” preparing for a real “Black Swan.”

An article written by iugitas, published on 24 July 2020

Translated by Charlotte Ley